Camille: 905 millibars

THIS IS HISTORICAL WEATHER INFORMATION FROM 1969. SCROLL UP FOR CURRENT INFORMATION ON ANA AND BILL.

On August 16, 1969, National Hurricane Center Director Robert Simpson needed information.

He knew that he had a hurricane captive in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. There was no way for the storm to go without hitting some landmass. He knew there was an upper level disturbance scooting toward the southeast from the Central Plains. That should turn the hurricane north and eventually northeastward.

Just on that basis, a hurricane watch was ordered along the Gulf Coast from Biloxi to St. Marks at 8 a.m. CDT.

He knew that people along the coast had to begin preparing. Lessons had been learned from 1957’s Audrey. Storms speed up and intensify rapidly.

The problem was, Simpson didn’t know how bad the hurricane was. In his gut he knew, but some forecasters believed it was weaker based on surface observations and rudimentary satellite photos. It was not yet in the range of coastal radars.

He knew that sea surface temperatures were warm. He knew that upper level winds were favorable for strengthening.

Simpson needed the best tool available…recon. But all the planes were flying in an experiment called Project Stormfury in Hurricane Debbie, trying to mitigate the power of the monster storms.

He had coaxed the Navy into dispatching an aging Super Constellation out of Jacksonville just after midnight Friday night while the storm was near the western tip of Cuba. The turbulence was so bad that the crew had to turn back.

But now, Simpson was flying blind. He called the Air Weather Service in Illinois. He got hold of a General who grasped the seriousness of the situation.

An Air Force C-130 was dispatched.

Advisory responsibility transferred to the Weather Bureau office in New Orleans for the 11 a.m. CDT when a hurricane warning was ordered from Fort Walton to St. Marks on the Florida coast. Preparations began in earnest. To the west, on the Alabama and Mississippi coasts, a hurricane watch was in effect, but people went about their business expecting the storm to head east.

In New Orleans, at WDSU, Nash Roberts warned residents of Southeast Louisiana not to let their guard down, that the hurricane was likely going to go more west than thought. Fortunately, Wade Guice, the Civil Defense Director in Biloxi heard Nash’s doubts.

Meanwhile, in Miami, Simpson anxiously awaited data from the plane.

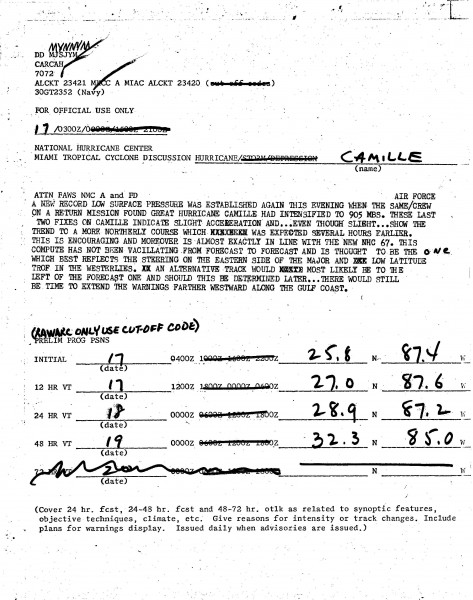

Just after 1 p.m. CDT, Simpson nearly dropped the microphone when crew radioed back the data after penetrating the eyewall. He asked for a repeat of the information.

908 millibars. It was the lowest pressure ever observed by a reconnaissance plane in the Atlantic.

The 5 p.m. advisory underscored the danger of the storm and its 150 mph winds. There was no question about the severity of the storm. Now where was it heading?

Forecasters waited for the much anticipated northerly turn. It didn’t come.

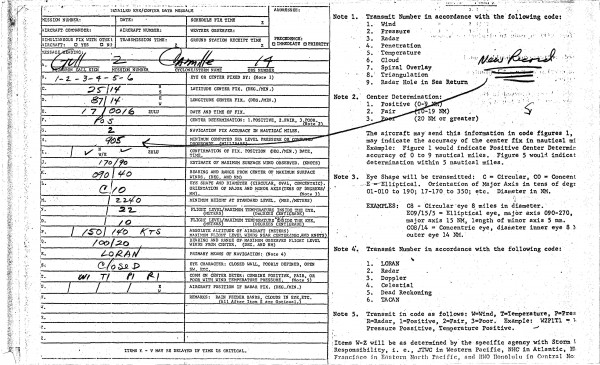

Just after 7 p.m. CDT, Gull 2, the Air Force plane that had found the record pressure earlier in the day penetrated the eye again.

The pressure reading was even more jaw dropping. 905 millibars. A new record for recon. In fact, in the Atlantic, only the 1935 Labor Day hurricane had sported a lower pressure (892 millibars).

People along the Mississippi coast staying up late that night might have been confused by the 11 p.m. advisory, which still said the storm threatened the Northwest Florida coast. Nash Roberts was still warning of a more westward track.

In the 10 p.m. discussion, forecasters at the National Hurricane Center indicated relief that the northerly track seemed to be materializing. It wasn’t. Internally, they were very concerned that the trough might miss the hurricane and the dreaded more westerly track might be realized.

Their fears would soon be realized.

Category: Uncategorized