Overrunning – The Rainmaker

You’ve heard us meteorologists talk about rainfall caused by “overrunning”, to the north of a front usually, for years. That’s what we’ve had going on since yesterday. Simply put, cold air is dense and stays near the ground, and warm, moist air blowing from the south often simply rises up and over that cold air near the surface, producing the lift necessary for rain.

But, on this blog we have started the category Meteorology 101, so we will start providing some more in-depth analysis on things like over-running (aka isentropic lift), and many other meteoroligical topics (Coriolis force, upper disturbances, jet streams and jet maxes, CAPE, helicity, gravity waves, thunderstorms, etc.), in the coming months, as the right time presents itself.

1. Potential temperature

The potential temperature of an air parcel is the temperature that parcel would have if it were brought adiabatically (without adding any nor removing any heat through condensation, evaporation, sunlight, etc.), to 1000 mb pressure (about at the ground). The potential temperature almost always increases with height. For example, on today’s BHM sounding, the potential temperature at 300 mb (30,000 ft., where an airplane may fly) is -29 F). When they bring this air in to pressurize the cabin in an airplane, it would naturally go up to 135 F! So, even though the air outside is cold, it has to be air conditioned when it is brought in because bringing it up to ground pressure increases the temperature so much.

2. Isentropic analysis

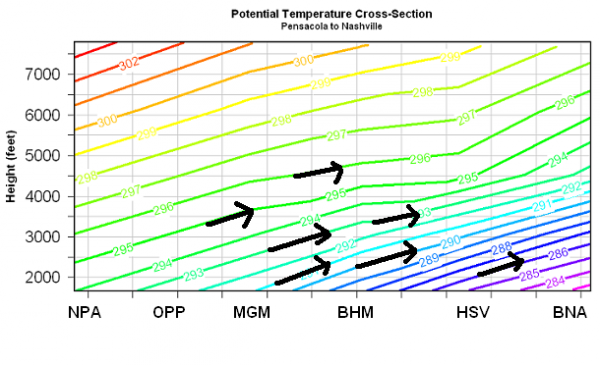

The potential temperature is also related to the temperature itself, since pressurizing can only cause so much warming. At low-levels especially, the colder it is, the higher you have to go to get to a given potential temperature, since the air colder to start with. From the side, a cold front looks like a wedge in potential temperature, since the cold air gets deeper further north behind the front, as shown in this cross-section (looking toward the west from Georgia) of potential temperature lines from the Gulf to Nashville yesterday.

Notice how the lines of constant potential temperature slope upward into the colder air. Now, this is the important part. Recall that potential temperature remaining constant means no heat is added to or removed from the air (no entropy change)? So, unless there is a heat source, the natural way for a parcel of air to move is along a line of constant potential temperature, known as an isentrope (constant entropy). The heavy arrows are air motion. Winds have been out of the south mainly, so in this environment, the air, with little or no heat being added from the outside, moves along the isentropes, maintaining constant potential temperature. Therefore, with warm air moving in (warm advection), especially with a stalled front nearby, air rises, forming rain. It is one of the most efficient ways the atmopshere produces widespread rain.

This same phenomenon explains one reason it is hard for it to snow in Alabama. Often, the rain moves out as the cold air moves in. Imagine the above chart with a cold front and north winds. The air would try to move along the isentropes, downward, drying up any precipitation. Cold air advection is not generally favorable for snow…you usually need the cold air to already be here.

Any questions are welcome in the comments section!

Category: Met 101/Weather History

Comments (34)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post