1940’s Armistice Day Blizzard

Monday, November 11, 1940 was Armistice Day, the remembrance of the symbolic end of World War I. On the 22nd anniversary of the end of the war, two of the Allied powers were not at peace. France was under Nazi occupation and Britain was under air siege by the German Luftwaffe. Newspaper headlines in the U.S. recounted President Franklin Roosevelt’s Armistice Day message, which denounced the world’s dictators. A small story buried inside most papers told of new Japanese demands. It would not be long until America was drawn into the conflict.

Across the Upper Midwest, temperatures had been well above normal through the first weeks of fall. On the morning of the 11th, temperatures were in the fifties across the area, well above normal for the season. At 7:30 in the morning, the temperature at Chicago was 55F. It was 54F in Davenport, Iowa. Highs the day before had been in the 50s and 60s across the entire region. Hunters took advantage of the holiday and the extremely mild weather to take to lakes and rivers across Minnesota and Iowa. They were to be rewarded with an overabundance of waterfowl. Many would later comment that they had never see so many birds. The birds knew something most of the hunters didn’t. They were getting out of the way of the approaching storm.

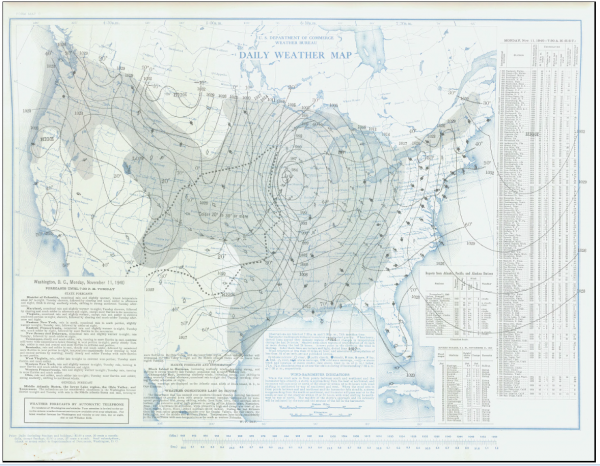

Weather forecasting was not a very reliable thing in 1940. There were no winter storm watches or blizzard warnings. The Weather Bureau did post a moderate Cold Wave Warning on the morning of the 12th, but Forecasts were only calling for a change to colder with snow flurries.

But all it took was one look at a home barometer to know something was up. The needle was nearly off the dial at places like Des Moines, where the pressure stood at 29.09 inches. At Charles City, Iowa, it bottomed out at 28.92. While it was 54F at Davenport, Iowa, it was 12F at Sioux City on the other side of the state.

Something bad was in store. A perfect storm was brewing, with warm Gulf air racing into the vortex, where it mixed with extremely cold Canadian air. The Weather Bureau office in Chicago, however, was not staffed at night. So no one saw the rapidly exploding storm.

As hunters sat in blinds or in their boats, a line of dark clouds approached from the west. It began to rain and the wind began to roar. The temperature dropped like a rock and the rain quickly changed to snow. The mercury would fall forty degrees in just a few hours from the 50s to the single digits. The snow fell with a vengeance. Blizzard conditions rapidly developed.

When it was all said and done, 26.6 inches of snow had fallen at Collegeville, Minnesota. Furious winds up to 60 mph whipped the heavy snowfall into drift twenty feet high. A total of 154 people perished in the terrible storm. Over twenty were hunters who froze to death when they found themselves trapped in the onslaught of the ferocious storm.

The U.S. Weather Bureau was roundly criticized after the disaster. Congressional inquiries would lead to significant changes, including offices that were staffed full time.

Category: Met 101/Weather History